Arroyo Grande History

The Architect

The Mad Blogger

USS Nevada, December 7, 1941

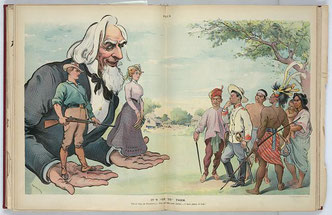

One of Arroyo Grande's connections to the Philippine Insurrection

The Collection

A collection of essays on history, including Arroyo Grande history, teaching, family and ancestors, the impact of war and the contributions of immigrant to local history.

How to Write Local History That Isn't (Local)

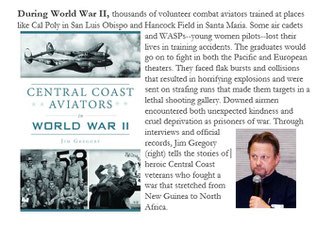

Aviators, from The History Press

"Yanks"

from Central Coast Aviators in World War II

This royal throne of kings, this sceptred isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars

…This precious stone set in the silver sea

…This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England.

Shakespeare, King Richard II.

If there was a military historian with a gift to rival Shakespeare’s, it was another Englishman named John Keegan. Keegan was a little boy in the English countryside when the Americans began to arrive in their numbers in late 1943 and into the spring of 1944. Little English boys had lived for years with the deepest of privations—thanks, in large part, to the U-boat campaign that had nearly starved Shakespeare’s “sceptred isle” to death—and then the Americans came. Keegan was many years later narrating a history of the Great War, about the impact of the arrival of an earlier generation in the pivotal spring of 1918, when he was suddenly at a loss for words. “Well,” he said finally. “they were Americans!” By which he meant they were boisterous, cocky, well-fed, well-clothed, and, thank God, they were friendly, with an innocence and immediacy that was distinctly American. They taught English boys baseball and flirted with their big sisters, who had suffered years of a different kind of privation, and married some of them, but most of them not, which meant that little boys Keegan’s age would inherit littler half-Yank nieces and nephews. Most of all, they were generous. There seemed to be no end to their Hershey bars (there wouldn’t be after the war, either, when, during the Berlin Airlift, one of bomber pilot Jess Milo McChesney’s comrades, Gail Halverson, air-dropped Hershey bars, floating on little parachutes, to the hungry children of blockaded Berlin) and no end to the rough affection for children that came with these big, loud men from across the sea.

And then they were gone. Keegan has vividly described the early-morning dark when that happened, when the Edwardian chinaware and modest crystal on every shelf in the Keegan home began protesting, rattling an alarm so loud that it woke the family up, if the motion beneath their beds hadn’t already made them sit bolt upright. The anxiety of Keegan’s family, and their neighbors, and of other families all across East Anglia, was relieved only when they went outside. Then anxiety gave way to wonder. They could feel in their breastbones the vibrations of the engines of thousands of airplanes, but could see only dim red and amber lights in the sky, bearing east, toward France. Some of the Americans Keegan had grown to love so quickly, his heroes, were on those airplanes, and tens of thousands of more, his heroes, were riding deathly pale on landing craft corkscrewing in foul Channel waters, and they were all headed for Normandy.

It was D-Day.

Doña Maria, 1849

Her full name was Maria Ramona de Luz Carrillo Pacheco de Wilson. I think. I accidentally found this photograph of her, age 37, while I was looking for something else entirely, which is how I usually find the material I need the most for writing history.

It’s a puzzler, that.

She, more importantly, was born a Carrillo, in San Diego, which immediately assigns her a special place in our history. There was no family more prominent in Mexican California. Her father was the commandante of the Santa Barbara Presidio, her son would become the twelfth governor of California, and her (second) husband, Yankee sea captain John Wilson, owned the lengthily-named Rancho Canada de Los Osos y Pecho y Islay, which translates in modern terms, to pretty much everything between Montana de Oro and Cambria.

Owning that much land boggles my mind. I grew up on three acres, and thought that much land immense.

Here is the point: She is, at 37, a handsome woman. It is difficult to imagine the self-assurance a man must have felt with a woman like this on his arm.

And she must have been, at sixteen, a delight.

To watch her dance must have been mesmerizing, and Californio women didn’t expend that much energy at fandangos. Dancing was prized, but it was a male pursuit. Young men, and even older men, like Juan Bandini, reputedly the best dancer in Mexican California, did the dancing, like Mick Jagger roosters on Dexedrine, and sixteen-year-olds like Maria moved chastely and modestly, their lacquered Chinese fans held aloft and their long lashes cast downward, while the young men, as is the the perfect right of young men, made fools of themselves in public.

Even Maria Ramona’s downcast eyelashes, I believe, must have been devastating. I would consider giving one or more arms to get the chance to go backward in time to see her at sixteen.

But this photograph–undoubtedly, part of a group portrait, because you can detect, at lower right, the wedding lace or First Communion lace or the quinceañera lace of another woman–is a revelation. It’s one more reason why I love women. I don’t “cherish” them. You don’t “cherish” a human being who can give birth to another human being with the density of a bowling ball and the kinetic energy of a herd of buffalo on the Yellowstone. No. You love them. You acknowledge your own gender's fragility, then you move on, loving them, and trying to keep up with them.

Maria, for example. She was born in 1812 and died in 1888, the same year my two-room school, Branch School, was built. When my parents drove me to that school for the Hallowe’en carnival (Houses were too far apart in the Upper Arroyo Grande Valley for trick or treating. You’d wind up in Pozo.), I could see, in the limbs of California oaks, bandidos reaching to snatch me from the car, especially if the moon was full. There was always history, in my little-boy imagination, just beyond the moonlight.

One of my first memories in the Valley was that of the home of another Californio matriarch, Manuela Branch, as it caught fire, about 1958, in the corner opposite the Valley from our home on Huasna Road. I had never seen anything burn so bright, and it would take me a few years to realize how costly that fire had been, how completely it had erased the traces of a woman so important. She was buried over the hill from our two-room school, alongside her husband--from Scipio, New York, of all places–-and alongside him, three little girls taken by smallpox in 1862, and, a few yards beyond their tombstones, the common tombstone of a father and son lynched in 1886.

How did they endure? Maria Josefa Dana gave birth to twenty-one children and lost more than half of them at birth or within five years. Nine of Manuela Branch’s survived, but she lived thirty-five years beyond her husband, who died in 1874. Maria Ramona de Luz Carrillo Pacheco de Wilson’s progeny was modest by Californio standards: seven children, but three of them would die before they’d reached twenty-five.

So here she is, in 1849, looking squarely at the photographer without flinching, and this was an age when the camera lens remained open so long because the “film” in those days, on glass-plate negatives, was so slow, that chancing a smile, even a faint one like hers, likely meant that her face would be lost to posterity. It would be a blur. Matthew Brady, in his Washington City studio, kept on hand a variety of neck and head braces, reminiscent of the Inquisition, to keep his subjects, including Lincoln, perfectly still.

And here she is, smiling, albeit faintly, like some kind of San Luis Obispo County Mona Lisa.

What is she smiling about?

It is, more than likely, an event in which she is a peripheral character. If it is a First Communion, a quinceñeria, or a wedding, it is certainly not hers. She is merely a guest. But the fact that she is included, even at the edge of what seems to be a group photo, one in which the celebrants wanted her presence, is indicative of her prominence and indicative of so much more: her personal strength, her unshakable calm, her dignity, and, most of all, her integrity.

You cannot “cherish” a quality like integrity.

You either understand it, or you don’t. This woman was bred into it, born into it, grown into it, and she would impart it in the generations who lived far beyond her death in 1888.

Her husbands were lucky enough to live with it, and with her.

She lived a life as strong as Christ’s rock—Jesus, fond of puns, changed Simon’s name to Peter, or “rock”—and soft as velvet. This is a proud woman.

She has every right to be.

To the Editor, 2002. On Beavers.

TO THE EDITOR, SAN LUIS OBISPO TRIBUNE:

Mr. Phil Christie of Cambria, in an April 9 Letter to the Editor on the Pismo Beach beaver situation, wanted to know if there were other beavers in San Luis Obispo County. The scientific answer is: Yup.

At least there were when I was a teenager, which was about the same time my close

personal friend, Sir Francis Drake, was bumping around the coast on the Golden Hinde.

Actually, it was only the mid-1960s. But there was a beaver dam on the Arroyo Grande Creek, adjacent to Kaz Ikeda’s cabbage fields in the Upper

Valley. I know because I fished in their pond. When I first found them, they were Angry Beaves (a popular cartoon show I used to enjoy with my sons when they were younger), but they soon became,

if not mellow, at least tolerant of my presence. Theydo slap their tails on the water, by the way.

I wore out my welcome one day when a late-afternoon shaft of sunlight hit the pond at

just the right angle, making the water translucent. There, meticulously aligned like a trout armada—I must be thinking of Drake again—were dozens of rainbows, noses upstream, waiting for me to

catch them. I was ecstatic!

So, as a crack fisherman, my first move was to fall into the water with rod, tackle and some happily liberated night crawlers.

I think I hear the beavers trying to suppress hysterical laughter. My dignity was crushed, so I never went back to the pond. I’m sure, however—if there are still beavers in the county—that this anecdote has been passed down from generation to generations around whatever is the beaver equivalent of a campfire. Stupid humans.

Jim Gregory

by Jim Gregory

Award Winner

2018 National Indie Excellence Award

Women's Airforce Service Pilots (WASPs). Three Central Coast women flew military aircraft during World War II. One of them, Betty Pauline Stine of Santa Barbara, was killed in the line of duty.

Pearl Harbor's Impact on Arroyo Grande, California

Just before eight o’clock on December 7, 1941, a bomb’s concussion on Arizona’s stern blew the lifeless body of Navy bandsman Jack Scruggs into Pearl Harbor. A little more than five minutes later, the second, fatal, bomb penetrated the teak deck, killing a second sailor, Wayne Morgan, and nearly 1200 of his shipmates when it detonated the forward powder magazines. Scruggs and Morgan had grown up in Arroyo Grande, a farm town in San Luis Obispo County.

Park Service divers can still see, just behind portholes, December 7 air trapped inside Arizona’s submerged compartments. A clock recovered from the chaplain’s cabin was frozen at just past 8:05 a.m., the moment the ship blew up.

Few moments can be frozen in time. History is remorseless and it demands change. The war changed Arroyo Grande forever. In a way, the little town of just under 1100 people was torn apart just as Arizona had been.

Residents here heard the first bulletin at about 11:30 a.m., as they were preparing for Sunday lunch, the big meal of the day for churchgoers like Juzo Ikeda’s family. Like many of the town’s Japanese-American residents, the Ikedas were Methodists. They were also baseball fans. Juzo’s sons had played for local businessman Vard Loomis’s club team, the Arroyo Grande Growers, and for Cal Poly.

Juzo was technically not “Japanese-American.” He was not permitted citizenship. The Supreme Court maintained that this honor was never intended for nonwhite immigrants.

The court couldn’t deny citizenship to Juzo’s sons, born Americans, or to the sons and daughters of families like the Kobaras, the Hayashis, the Fuchiwakis, the Nakamuras.

These young people played varsity sports at the high school on Crown Hill, or served in student government or on The Hi-Chatter, the school newspaper, or joined the Latin Club or the Stamp Collecting Club, the brainchild of young cousins John Loomis and Gordon Bennett, known for committing occasional acts of anarchy as little boys (John’s mother grew so frustrated that she once tied him to a tree. Gordon freed him.) and known even more for being good and loyal friends.

Two of those friends were Don Gullickson and Haruo Hayashi. Loomis, a Marine, and Bennett and Gullickson, sailors, would fight the Japanese in the Pacific in the last year of the war. They would also continue to write to Haruo at his internment camp at Gila River, Arizona.

Haruo joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, but he was very young—only a sophomore when Pearl Harbor was attacked—and the war ended before he could ship out for Europe.

Haruo never understood an incident at the 442nd’s training camp at Camp Shelby, Mississippi. A wonderful USO show arrived and while both the white and Nisei GI’s watched it in the camp auditorium, black GI’s had to content themselves with hearing what they could of the show while standing outside.

It wasn’t right, Haruo thought.

In April 1942, buses had appeared in the high school parking lot atop Crown Hill to take Haruo and his family to the assembly center in Tulare. A line of teenaged girls—twenty-five of the fifty-eight members of the Class of 1942 were Nisei—walked up the hill together to where some would board the buses. They were holding hands. They were sobbing.

Many young men would join the army after they and their families were moved to the desolate Gila River camp. Sgt. George Nakamura won a Bronze Star and a battlefield commission to lieutenant for rescuing a downed flier in China. Pfc. Sadami Fujita won his Bronze Star posthumously. German small-arms fire killed him as he brought up ammunition during the relief of the “Lost Battalion” in France in 1944. Nearly a thousand Nisei GI’s were killed or wounded in freeing the 230 young Texans pinned down in dense woodland splintered by German shellfire.

When Sgt. Hilo Fuchiwaki first came home at war’s end, he went to the movies in Pismo Beach in his uniform. A patron spat on him. When the Kobara family came home from the Gila River camp, they could hear gunshots in the night as they slept, for protection, in an interior hallway of their farmhouse.

As others began to come home, they found that families like the Loomises, the Silveiras and the Taylors had watched over their farmland and farm equipment. Insurance agent and football booster Pete Bachino, killed in the 1960 Cal Poly plane crash, had taken care of their cars.

But more than half of Arroyo Grande’s Japanese-Americans never came home again.

Arizona, twisted grotesquely at her mooring, burned for two days after the Pearl Harbor attack. The scar that this terrible fire left behind, even here, seems invisible only because it is so deep.

Power Struggle in the Fields

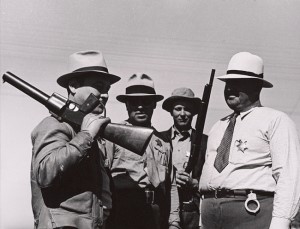

This photo reminded me immediately of Rod Steiger's superbly-acted redneck sheriff in the film In the Heat of the Night. But these are Californians, not Mississippians, and these men, according to the scholarship I've been trying to digest so far, were representative of an alliance of reactionary forces that dominated California between 1933 and 1938.

Whether they were representative of San Luis Obispo County remains to be seen.

What made up that coalition? To borrow Renault's quote from Casablanca, they were the usual suspects: Harry Chandler's L.A. Times, the Hearst newspapers, the L.A. District Attorney and the LAPD, the Chamber of Commerce, Pacific Gas and Electric Co., and Associated Farmers, a powerful anti-labor lobby (they blocked literally hundreds of bills in the state legislature that would have provided laborers with a minimum wage, with decent housing, even a bill that would have required employers to provide drinking cups) that also organized resistance to and suppression of strikes.

They wore revolvers on their hips, however, like Henry Sanborn, a national guard officer who organized hundreds of paramilitary "deputies" in the 1936 Salinas lettuce strike, a strike provoked by the growers themselves when they locked workers out of the packing sheds. The growers, in fact, had already built a big stockade, complete with concertina wire, in anticipation of a strike. "Don't worry," they told alarmed packing-shed workers before the lockout. "That's for the Filipinos."

By the way, the one dissident in the state's economic power structure, an ardent New Dealer, was A.P. Giannini, founder of the Bank of Italy, by now the Bank of America.

Another disturbing trend was the extent to which this coalition depended on the newly-founded California Highway Patrol. In Salinas and other places, including in a brief mention in an article about Nipomo, the CHP constituted a kind of rapid-repsonse strike suppression force and one, unlike the "deputies" and their baseball bats in Salinas, that was heavily armed.

In the history of American labor disputes, like the 1894 Pullman Strike, this traditionally had been the role of government: to uphold capital and to suppress labor. TR's intervention in the 1902 Pennsylvania Coal Strike represented a rare departure, because he demanded that both sides come to the bargaining table or he'd use the army to take over the mines. Neither management nor labor were pleased with the president, but the strike was settled.

When TR's cousin became president, capitalists, including California growers, were outraged that the government seemed to side so clearly with workers, what with the Wagner Act (which did not extend to agricultural workers; FDR didn't want to alienate Southern Democrats and their planter-supporters), with health inspections of labor camps, and with occasional attempts by the federal government to settle strikes (one such attempt had a Labor Department official beaten, stripped, and left in the desert of the Imperial Valley).

The Arroyo Grande Herald-Recorder at this time regularly railed against the excesses of this activist government on its editorial page while its news page primly reported another schedule of AAA subsidy payments.

Frustrated as they were with FDR, growers and their allies obviously took on the strikers, not the federal government.

The easiest way to sanction strikers, and to make labor organizers "disappear" (Temporarily. Usually.) was to arrest them for vagrancy, since they clearly weren't working. That was the pretext used by SLO County Sheriff Haskins, backed by 200 instant deputy sheriffs, in the 1937 pea strike, in April. It worked; that strike, centered in Nipomo, ended pretty quickly. So had another one farther north, in January, in and around Pismo Beach, organized by Filipino laborers against Japanese growers. It was over in three weeks, with some violence--fights between strikers and scabs--and it ended with a negotiated settlement. The growers didn't negotiate with the strikers, by the way. They negotiated with the Chamber of Commerce, which dictated the settlement. Curious.

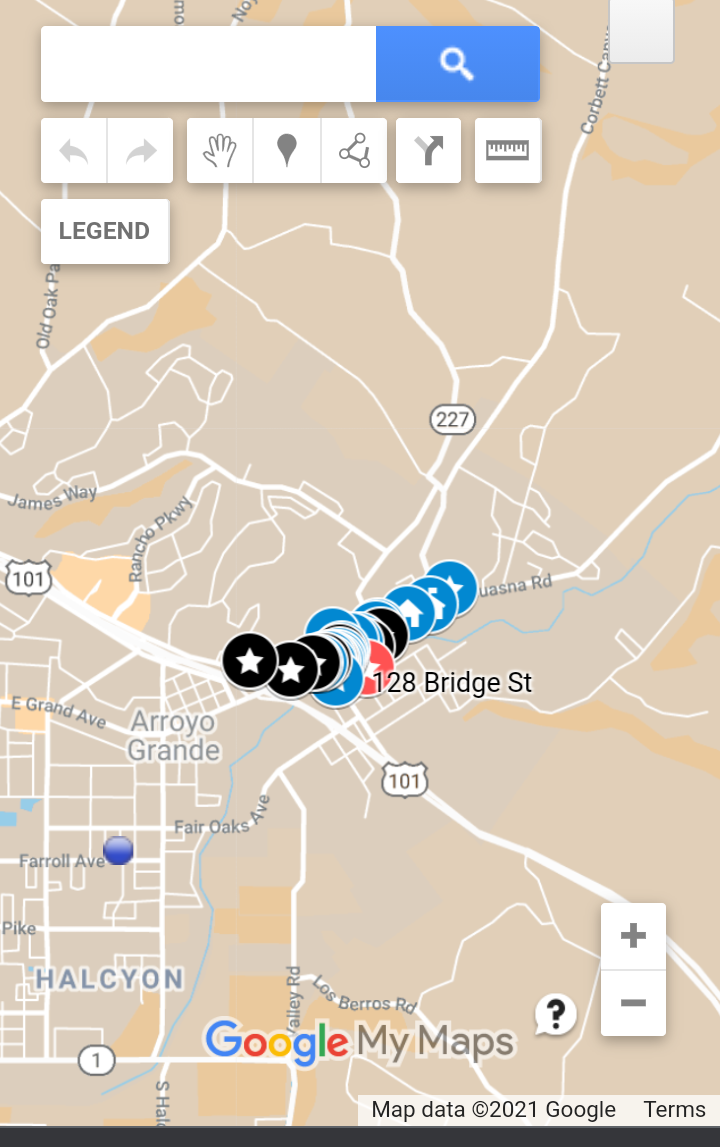

Branch Street, Arroyo Grande, California: Some of the stories behind a farm town's main street

Santa Maria Times photo by Ian Wood.

"Glimpses of Arroyo Grande's History"

A series of four videos addressing topics in local history, 1837-1945.

Good Neighbors

Click on the link below for inspirational stories from Arroyo Grande's past.

Our History Museums

Interactive Map: Branch Street, Arroyo Grande

About Jim

Jim Gregory taught American literature, modern world literature, cultural anthropology, advanced placement U.S.

history and AP European history for thirty years at Mission College Preparatory School in San Luis Obispo, California, and at Arroyo Grande High School. He, with his brother and two sisters, was

raised in the Upper Arroyo Grande Valley and attended the two-room Branch Elementary School. He then studied journalism and history at Cuesta College; the University of Missouri-Columbia, where

he received his bachelor's degree; and California Polytechnic State University-San Luis Obispo. He was an editor at ABC-Clio in Santa Barbara and a newspaper reporter in San Luis Obispo before

becoming a teacher. He has also worked as a research historian for the San Luis Obispo County Historical Society.

Jim was the Lucia Mar Unified School District's Teacher of the Year in 2010-11. In 2004, he received a

Gilder-Lehrman Fellowship to study the Depression and New Deal with Pulitzer Prize-winning Stanford University professor David Kennedy, an experience that only deepened his fascination with the

1930s and 1940s. He has led several student trips to Europe, including visits to many of the villages and cities where young Americans fought in 1944-45. He recently taught a class on descriptive

writing for young people as part of the Central Coast Writers Conference in San Luis Obispo. Jim is married to Elizabeth, a teacher and campus minister at St. Joseph High School in Santa Maria,

and the father of two sons, John and Thomas. The Gregory family shares increasingly precious space in their Arroyo Grande home with one Basset hound, two Irish setters, one tortoise and a small

army of cats.

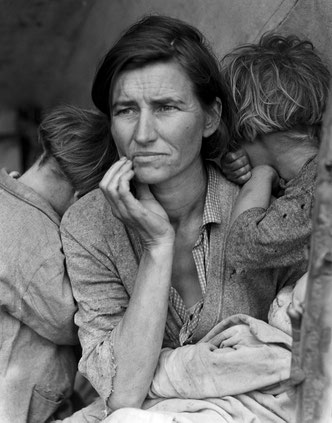

The Photographer

In 1936, the woman’s beret and mannish dress—oxford shirt, pleated skirt, sweater tied around her shoulders, high-topped tennis shoes—might have made her look a little like the outlaw Bonnie Parker. The car she drove was a powerful V8, the engine Bonnie and Clyde favored, but her car was homely and utilitarian, a wood-paneled Model C Ford wagon, not sleek and raked like the Ford DeLuxe in which the outlaws had met their deaths two years before.

The driver, nodding a little with each click of the seams in the two-lane concrete Highway 101, needed a wagon's room, not for bank-bags full of loot, but for equipment, the boxy, awkward but fragile paraphernalia of the documentary photographer, tucked securely inside the passenger cabin and wedged together in cases to make the run north to San Francisco secure and tight.

She had a good six hours to go before San Francisco and so was taking a chance on dubious tires on the narrow coast highway, littered in sad little Darwinian islets with expired possums, skunks, and ground squirrels. For her, the more menacing detritus was that of a nation in motion: fragments of glass, shredded and peeled truck-tire treads, oil slicks, fragments of cargo that included scraps of lumber and tenpenny nails. Her tires, nearly bald at the edges from months of traveling hard roads in the San Joaquin Valley and the California coast, were vulnerable to the traps the 101 had laid for her, but she wasn’t prepared for the trap the roadside sign presented.

PEA PICKERS CAMP

At first, she was strong enough to resist the seduction of the crudely-lettered sign; she had so far to go and had, after all, only reached the southern edge of San Luis Obispo County. Here the terrain was just beginning to reveal that she’d left the gravitational pull of Los Angeles, which ends at about the Gaviota Pass, with its severe rock outcroppings scattered with spiny yucca plants, where the light hits hard at noontime and yields to soft pastels at sunset, purples and pinks, all suggestive of aridity and drought in a country meant for lizards and coyotes and not for farming.

She knew the farmland she was entering pretty well, had interviewed and talked to its Mexican migrants and itinerant cowboys and the gypsy people mistakenly generalized as “Okies,” “mistaken” because she’d photographed the same kind of people from as far away as Vermont. They lived in their canvas tents and lean-tos in labor camps like the one the cardboard sign suggested, and they were as hard and as stark and as dry as the rocks at Gaviota. Poverty and stoop labor and hunger and human hostility had dried these people out by 1936. If the woman had her way, hope would wash through them like irrigation water the color of creamed coffee did through the furrows of the fields they worked, fields of pole beans and strawberries, cabbages and peas. But this water would revive them, fill them out, galvanize and energize them, restore to them the forward-looking strength that had been so fundamental to their ancestors from Germany, from the Scots Lowlands, from Sonora and Mississippi, from Luzon and Kyushu. These people waited, quiet, stoic, unblinking, for the waters of hope to baptize them. But they thirsted for them.

She kept driving north past the irrigated fields and vast groves of fruit and walnut trees because there was no need for her to stop. On the seat and the floor beside her were thousands of 5 x 7 negatives secure inside their wooden frames, stored in black light-resistant boxes, and on that film she had captured the hard, dry, and thirsty people at work in their fields, in camps preparing dinner or washing laundry, and their children beside them in the fields, whole families struggling with the trailing bags they were struggling to fill with cotton bolls or onions or potatoes or with the tall wooden pails meant to be filled with fruit or pea pods. They harvested the food that fed a nation that was now too incapable or too unwilling to feed migrant farmworkers.

Their children’s bellies were swollen, their legs were like sticks, knock-kneed from rickets, and now, in the hard rains that had come late this year, the dominant sounds that came from the tents in the migrant camps were the wracking coughs of migrant children in attacks that convulsed them and curled them like sowbugs into the fetal position where they could gather enough strength for another breath. There were thousands of people like these harvest people, sealed in her negatives on the seat beside her, waiting to come to life again in tubs of fixer in the photo lab.

Some of them, some of those children, were going to die.

South of the Ontario Grade, to her left, was a stretch of the Pacific in a shallow crescent from Guadalupe to Port Harford; the sight of it must have hurried her north to where she would finally see the ocean again, and with it San Francisco.

Ten minutes later, impulsively, somewhere near San Luis Obispo, the driver pulled to the shoulder and stopped her car.

The engine idled and her grip tightened atop the steering wheel. She leaned forward until her forehead rested against her knuckles and she closed her eyes. She was tired. She had miles and hours of highway ahead of her before home and relief and release from the hard work she’d been doing.

Then she sighed.

There was only one thing to be done. She brought the Ford around in a U-turn and headed south on the highway she knew so well that she would intuit a mile ahead of its appearance where the sign would be, where she would turn off the 101. She could not know it now, a little angry at herself for reversing course, but when she turned off she would meet a Madonna of the Sorrows, a woman in a tent in a muddy field who would leave even a master like Raphael rapt in her presence and powerless to capture her image. This image was meant for the photographer, and meant for her alone.

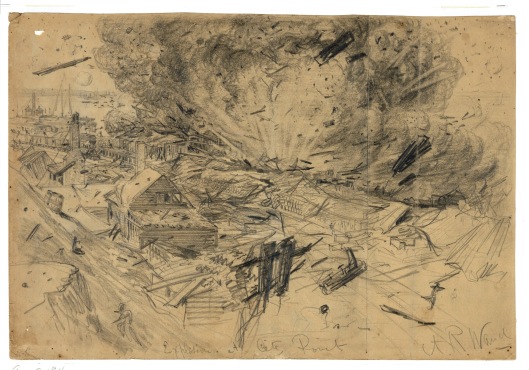

An Arroyo Grande Civil War Veteran: The explosion at City Point

...City Point, Virginia, was Grant’s supply base the last year of the war. It would would have astounded the men at Gone with the Wind’s barbecue because of its acres of artillery parks, stacked cannonballs, warehouses full of shoes, Springfield rifles, boxes of hardtack—the army cracker almost durable enough to build a home, and just as indigestible—row after row of tents in a city of soldiers, even its bakery, capable of turning out 100,000 loaves of bread a day. Quartermaster wagons offloaded cargo along a river controlled by navy ironclad gunboats; the wagons traveled in a never-ending stream so busy that it might have reminded the gentlemen from Margaret Mitchell’s Georgia of worker ants, charged with energy and purposeful.

Wharf, City Point, Virginia

By 1865, even Lincoln’s presidential yacht, the River Queen, was anchored in the river when he visited with Grant and Sherman to sketch out the final acts of the war. Lincoln treasured these trips to see his soldiers, away from the constant assault of favor-seekers who paraded through his office. On another visit earlier in the war, to McClellan’s headquarters, Lincoln had idly picked up an ax on the deck of the Treasury Department yacht Miami, smiled, and lifted it, holding it straight out at arm’s length for several moments. None of Miami’s sailors, when they attempted it, could do the same. On April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth’s bullet would traverse Lincoln’s brain; logically, it should have killed him instantly, so it was only Lincoln’s will and physicality that allowed him to live for nine hours after the shot had been fired. George Monroe, another Arroyo Grande settler, would have felt the president’s loss in a very personal way: the 148th Ohio Infantry and Pvt. Monroe had been the recipients of a thank-you, a short Lincoln speech, in August 1864.

Even though Monroe and his comrades were short-termers—100-day men, usually relegated to guard duty on railroads, at strategic bases like City Point, or as support troops—the 148th, came close, thanks to the spectacular attempt at sabotage, to never seeing Lincoln at all. On August 9, 1864, two Confederate secret agents penetrated the picket line that surrounded the wharves simply by crawling through it on their hands and knees. The letdown in security might at in part be traced to the heat that day. City Point’s pickets may have found themselves dulled by the kind of torpor ninety-eight-degree temperatures can induce. Even the stoic Grant found it hard to deal with the heat; he emerged from his tent and was doing his paperwork in his shirtsleeves.

Grant, his son Fred and his wife Julia at City Point.

While Grant was at his labors, the lead Confederate agent, John Maxwell, left his companion behind and approached a barge, the J.E. Kendrick. From Maxwell’s report.

I approached cautiously the wharf, with my machine and powder covered by a small box. Finding the captain had come ashore from a barge then at the wharf, I seized the occasion to hurry forward with my box. Being halted by one of the wharf sentinels I succeeded in passing him by representing that the captain had ordered me to convey the box on board. Hailing a man from the barge I put the machine in motion and gave it in his charge. He carried it aboard.

The hapless man from the barge did not know that he’d just been handed–Maxwell’s “machine”—was a time bomb, packed with about twelve pounds of explosives. Maxwell and his accomplice did not know, since they were attempting both nonchalance and rapid flight at the same moment, that the box they’d delivered was now aboard an ammunition barge.

Artist’s conception of the August explosion.

What a Union soldier heard, ten miles away, in the trenches outside Petersburg, Virginia, was like a thunderclap. What a group of officers near Grant’s headquarters heard in the middle of their poker game was a cannonball ripping through the canvas of their tent, from one side to the other, after the explosion had sent it flying. What a soldier felt was immense pain at the sight of a white horse, on which a woman had been seated at the moment of the explosion. The woman was gone, and a Whitworth bolt—a shell from an artillery rifle—had gone through her horse, now standing, shivering in shock. The soldier held the muzzle of his rifle next to the animal’s head and fired. What a woman on a riverboat nearby felt was a dull thud on the deck beside her. She noticed it was a human head. She picked it up by its hair and placed it carefully in a fire bucket full of water. The only other person as nonplussed as she was Grant, who looked with concern after some slightly wounded staff officers, gave a few orders, and returned to his paperwork.

The barge Kendrick was gone, as was much of the City Point wharf. So were unknown numbers of contrabands, former slaves who were working for pay as stevedores. Three members of Monroe’s 148th Ohio were killed, along with forty other soldiers, clerks and civilians, and over a hundred were wounded. The disaster was deemed an accident—not until after the war would it be revealed that it had been the act of John Maxwell, who escaped.

Nine days later, the wharf at City Point had been rebuilt and was as busy as it had been in the moments before Maxwell’s bomb had detonated. What happened at City Point was a tragedy, but it did nothing to stop the industrial machine that would continue to grind the Confederacy down. George Monroe and the 148th Ohio would soon be headed home; Adam Bair, the soldier who would settle in the Huasna Valley, and his 60th Ohio were three-year men, not 100-day men, and so they were headed for wherever Robert E. Lee was headed.

Reaction to Patriot Graves: Discovering a California Town's Civil War Heritage

“In our family, the Civil War had never been distant,” Jim Gregory writes, and he enlivens history with that same immediacy for his

readers, much as he did for generations of Central Coast high-school students. Animated by vivid anecdotes, Patriot Graves carries the reader from the battlefields of Pennsylvania to a

home for disabled veterans in Santa Monica to Arroyo Grande, the end of the “Westering” road for some of the formerly unnamed veterans whom Gregory restores to their place in the war that

changed the course of a nation. Gregory writes with enormous empathy but unflinchingly details the horrors of war and its aftermath. As the book’s title suggests, Gregory’s history is

specific and personal, populated with individual lives and personalities. At the same time, Patriot Graves is a story of rippling consequences and the effect that each individual life has

on the life of a nation.

--Susie Salmon, Assistant Director of Legal Writing; Clinical Professor of Law at University of Arizona James E. Rogers College of

Law

Patriot Graves: Discovering a California Town's Civil War Heritage named a finalist for international book award

Photo by david midddlecamp.

BY KAYTLYN LESLIE

MAY 04, 2017 4:02 PM

Arroyo Grande author Jim Gregory’s latest book exploring the South County town’s close — yet somewhat unknown — ties to the Civil War is getting some international recognition.

Gregory’s “Patriot Graves: Discovering a California Town’s Civil War Heritage” has been named a finalist for the 2017 Next Generation Indie Book Awards, an international competition for independently published works. Gregory is a local historian and author of other nonfiction works including “World War II Arroyo Grande.”

The competition is the largest not-for-profit book awards program for independent authors and publishers, according to its website. It was established in 2008 to recognize and honor “the most exceptional independently published books in over 70 different categories,” and is presented by Independent Book Publishing Professionals Group. The competition has been labeled “the

“Patriot Graves” examines the exodus of both Union and Confederate soldiers to the West Coast, where many were instrumental in developing parts of California. (A fun tidbit from the book: Arroyo Grande High School owes some of its existence to the work of Erastus Fouch, a member of the 75th Ohio Infantry who fought at the Battle of Gettysburg.)

“I’m not going to say that they didn’t have struggles when they came out here,” Gregory said in a previous Tribune report. “But, man, if you just look at the families they raised and the descendants they left behind, it looks to me like a lot of them turned out pretty well. That’s something to be said for little old South County of San Luis Obispo.”

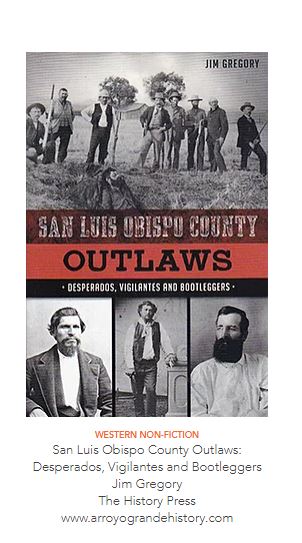

Gregory is currently working on his next book, “San Luis Obispo County Outlaws: Desperados, Vigilantes and Bootleggers,” which will examine some of the area’s most notorious and enigmatic criminals. He has also begun research for a separate work on the history of local aviation, with a focus on aviators during World War II.

Kaytlyn Leslie: 805-781-7928, @kaytyleslie

Reaction to World War II Arroyo Grande

Mr. Gregory is a phenomenal writer, and I wish he had written all the history texts I had to slog through in school. He brings the stories of a small town's contributions to the war effort to the level of exquisite storytelling. I don't say this lightly: his work is the quality of David McCullough with a good deal more wit thrown in.

--Mary Giambalvo

…this is an excellent read. Gregory superbly juxtaposes life on the Central Coast with that with places like Normandy, Iwo Jima, and at the internment camps throughout the United States. As an

Arroyo Grande native, I thoroughly enjoyed this perspective. Some references throughout will be significantly more meaningful to those from (or familiar with) the Central Coast of California.

However, this is an excellent piece of historical nonfiction, and I recommend to all interested in learning more about WWII.

Great history writers can turn statistics into meaningful stories, and Gregory shows a strong aptitude for this. In letters from home, newspaper articles, and war correspondences, he is able to

capture both the monotony of war, the heartbreaking losses of battle, and the amazing humanity of many individuals who helped those who lost everything.

Another recurring motif throughout the book is a sense of disturbance with the harsh realities of war. Gregory does not gloss over losses nor glorify victories during the war, and the reader is

left with a much better sense of what life was like from multiple traditionally marginalized perspectives.

This book focuses around Arroyo Grande, but the perspective could be swapped for any small town that had to overcome losses during the war. I highly recommend for anybody interested in developing

a better human-level view of WWII.

--Vince Joralemon

Jim Gregory is a wonderful storyteller and historian!

--Kay Lackey Orrell

Fantastic book! Makes history come alive. I will be up all night reading this gem. I am already looking forward to the next book by this very talented author.

--Cat Donovan